Protecting the iconic and sensitive landscape features on the Goulburn River, including The Drip, is a major campaign of MDEG and Mudgee Coal Alert. We are calling on the NSW Government to protect the water systems that feed The Drip Gorge and Goulburn River, both groundwater dependent ecosystems (GDEs) and the fragile cliffs and sandstone escarpments. This includes no longwall mining within 2 kms of The Drip Gorge and extending the Goulburn River National Park at least 1 km to the north and south of the river to create a protective buffer.

Why is it special?

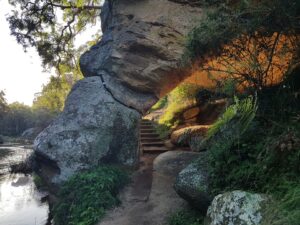

The Drip and Corner gorges of the Goulburn River form part of an ancient, visually dramatic landscape. Many visit this iconic and culturally significant place to experience its natural beauty and extensive Aboriginal heritage, walking along the Goulburn River or picnicking under soaring sandstone cliffs. Clear spring water drips and seeps through sculptural rock formations laden with ferns, bottle brushes and weeping grasses.

The Drip Gorge sits on the western most lip of the Sydney sandstone basin and on the lowest point of the Great Dividing Range. It is only a short walk (1.4 kilometres) from the Ulan-Cassilis Road and is widely used by the community, tourists and schools for recreational, educational and cultural purposes. It allows families to have a ‘wilderness experience’ similar to walks in the Blue Mountains Heritage Area or Northern Territory gorges.

There is also a recent coal mining history amongst these beautiful cliffs and river gorges. Prior to the 1980s a pit and prop coal mine, still using pit ponies to haul the coal, dug small quantities to supply the local hospital. In the early 1980s Ulan Coal Mine was expanded with the development of a large open cut mine followed by a underground longwall operation. This involved diverting 5.2 kilometers of the Goulburn River around the open cut pit.

What’s the threat?

Environmental impacts from open cut and underground mining threatens the long term health, resilience and viability of this river system. These include a rise in algal blooms promoted by the build up of clay and silt in the sandy river bed from the discharge of highly turbid water after storm events and ongoing legacy of the river diversion; significant increase in river salt loads and unexplained salinity spikes; plus the loss of groundwater base flows that maintain critical stream flows during extended dry periods. All examples of coal mining impacts that affect this sensitive environment.

Since 2004 two more mega coal mine developments were approved across the headwaters of the Goulburn River – Wilpinjong Coal Mine (Peabody) and in 2007 Moolarben Coal Operations (Yancoal). The current approved underground mining footprint in the Ulan Wollar area has grown to over 300 square kilometres with additional exploration areas (ELs) stretching over 164 square kilometres.

The current mines are licensed to extract is 65 ML/day plus including incidental take (interception) of surface and groundwater. In 2022 the combined water usage by Ulan, Moolarben and Wilpinjong coal mines was estimated at over 12,000 million litres (2022 Annual Review, by Ulan Coal, MCC; WilpinjongCoal).

All three mines have been granted pollution licenses by the government that permit offsite discharge of treated mine water and spillage from sediment dams. During 2022 the three mines discharged over 14,000 million litres of mine water offsite, carrying an estimated 13,500 tonnes of salt (2022 Annual Reviews – UlanCoal, MCC & WilpinjongCoal ). The chemical composition of saline mine discharge water can differ significantly to what naturally occurs in surface waters. Mine de-watering, seepage and the discharge of excess mine water in the upper Goulburn is increasing downstream salt loads, altering the natural flow regime, and changing surface and groundwater chemistry. The relative proportion of ions in saline waters as well as other co-occurring environmental stressors (e.g. turbidity) can have a combined greater effect on ecosystem health than total salinity (Kefford et al., 2013, Krogh et al., 2013). The impact of mine water discharge on macro-invertebrates and groundwater stygofauna requires further research.

Rehabilitation of massively disturbed mined land is a slow unproven process, so far no mined areas can be regarded as fully recovered to a mature forest ecosystem despite nearly 40 years since the commencement of the first open cut. The long term impact and future recovery of the groundwater levels is one of the key major issues facing the river system. Mine modelling predicts well in excess of 100 years until depleted levels may stabilise. Until then the river and dependent ecosystems will be robbed of crucial groundwater base flows, reducing their resilience and increasing their vulnerability to drought in the face of catastrophic climate change.

Threatened species at risk

The expansion of coal mining in this area has a significant negative impact on unique and threatened species and their habitat. The Moolarben Coal open cut and underground operations currently affects 226 hectares of the critically endangered White Box/ Yellow Box/Blakely’s Red-gum Ecological Community removing threatened species habitat for woodland birds, bats, owls and iconic native mammals.

The critical woodlands to be destroyed provide habitat for nationally listed endangered animal species including the Swift Parrot, Squirrel Glider, Painted Honeyeater, Hooded Robin, Diamond Firetail and the now critically endangered Regent Honeyeater. Studies have also identified the occurrence of habitat for the threatened Brown Treecreeper, Speckled Warbler, Gilbert’s Whistler, Glossy Black Cockatoo, Powerful Owl, Large Bentwing Bat, Large-eared Pied Bat and Greater Long- eared Bat and an emerging koala population. Foraging and breeding sites will be lost, especially from areas where there is a high density of tree hollows and forage trees.

The recently proposed expansion of Moolarben Coal Open Cut 3 includes five more opencut pits bordering the Munghorn Gap Nature Reserve. This expansion is of major environmental concern to both the community and NPWS. It requires the removal of critical woodland bird and koala habitat, will have a significant impact on the remaining cultural heritage and natural landscape in the upper reaches of the Moolarben Valley, and intercept and divert fresh groundwater sources from dependent ecosystems.

The cumulative impacts of coal mines

The impact of these three large and expanding mega coal mines in the Ulan Wollar area raises many questions about interference to regional groundwater and long term viability and integrity of the Goulburn River, a major tributary of the Hunter River. The estimated combined total water being removed from the groundwater system due to mining operations in the upper Goulburn ranges between 30 and 65 million litres per day.

The local community has regularly expressed their concerns about the risk to surface water and groundwater, damage to The Drip and Corner Gorges, impacts to groundwater dependent ecosystems, fears of local tourism industry decline, dust, noise and an overall inadequate assessment of cumulative and regional impacts associated with these three mining operations.

Recommendations

There is broad and enduring community and agency support for the protection of this highly valued and significant Drip Gorge riparian area and adjacent escarpments by incorporating this sensitive river corridor into the Goulburn River National Park. It is now widely accepted that the significant cultural, spiritual, historical, educational, tourism and recreational values associated with The Drip and the Corner Gorge should lead to their protection.

Moolarben Coal Mine underground 4 (UG4) has approval to mine within 200 metres of the river bed and 400 metres from the Corner Gorge. To provide adequate protection there needs to be a no-go mining zone that excludes all mining 2 kilometres from the Goulburn River in the vicinity of The Drip and Corner gorges and its inclusion into the national estate for the people of NSW.

The Government must take action to:

- Protect the Goulburn River and adjacent sandstone escarpments surrounding The Drip Gorge from mining by extending the Goulburn River National Park at least one kilometre either side of the river with 2 kilometre no-go zone for mining.

- Reform mining policy, the approval process and regulations on mining operations to ensure the highest standards of independence, probity and transparency

- Commission an Independent Regional Water Survey and cumulative impact study to determine the full environmental impacts of the three mines on groundwater and river ecosystems of the Upper Goulburn River catchment.

- Commission an independent study of groundwater dependent ecosystems and groundwater stygofauna in the Goulburn River and Moolarben Valley and investigate the long term effect of mine water discharge on ecosystem function.

Get Involved

There are several ways to get involved with the “Save the Drip” campaign

- Follow Mudgee Coal Alert

- Become member of MDEG

- Follow our Facebook community page “savethedrip'”

- Visit us at a Market Stall

References

Kefford, B. J., Miller, J., Krogh, M. and Schafer, R. B., 2013. Salinity and stream macroinvertebrate community structure – the case of the Hunter catchment, Eastern Australia, Report prepared for teh NSW Office of the Environment and Heritage,

Kellett, J. R., Williams, B. G. and Ward, J. K., 1989. Hydrogeochemistry of the upper Hunter River valley, New South Wales, Australian Government Publishing Service Canberra.

Krogh, M., Dorani, F., Foulsham, E., McSorley, A. and Hoey, D., 2013. Hunter Catchment Salinity Assessment: Final Report, Report prepared by Office of Environment and Heritage for the NSW Environmental Protection Agency Sydney, Australia. Available at: www.epa.nsw.au (accessed 20/12/2013).

Moolarben Coal Complex Annual Review 2022, Moolarben Coal Operations Pty Ltd; Yancoal (Aust),

MER, 2011. Environmental Assessment – Modification of Ulan Coal CONTINUED OPERATIONS – Appendix 3 Groundwater Assessment Report Xstrata Coal Toronto, Australia.

MER, 2015. Appendix 3: Assessment of Groundwater Related Impacts arising from Modifications to the Ulan West Mine Plan. , GLENCORE Ulan Coal Mines Ltd.,

Ulan Coal Mine Annual Review, 2022. Ulan Coal Mine Pty.Ltd – GLENCORE

Wilpinjong Coal Mine Annual Review 2022 and Environmental Management Report, Peabody Energy (Aust),